Vladivostok, Russia: Strategy of Cultural Heritage Protection and Use

Anna Myalk, Victor Fersht, and Victor Korskov. Translation by Zoya Proshina.

1. Brief History of the Regionís Development and Heritage

The Russian Far East is a vast territory of 6.1 million square kilometers, making up about a third of Russia. The Far Eastern Federal District of Russia stretches from the Bering Sea in the north, to the Sea of Japan in the south; in the east, its territory is bounded by the Pacific Ocean coastline. The district includes nine regions.

Regions of the Russian Far Eastern Federal District

Table 1.1

№

Geographical and administrative district

Area (thousand - sq. km)

Population (thousand people)

Capital

Year of capitalís foundation

Number of cultural heritage sites (number of revealed items is in brackets)

Local significance (architecture and history)

Federal significance

Architecture and history

Archeology

1

Primorskiy Krai

165.9

2,236.2

Vladivostok

1860

1615

126

1200

2

Khabarovskiy Krai

785.5

1584

Khabarovsk

1858

527

35

632

3

Amurskaya Oblast

363.7

997.5

Blagoveschensk

1856

434

9

183

4

Jewish Autonomous Oblast

36

209.9

Birobijan

1937

67 (4)

2

(37)

5

Sakhalinskaya Oblast (59 islands)

87.1

598.6

Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk

1882

150

-

250 (1100)

6

Magadanskaya Oblast

462.4

223

Magadan

1929

131

1

76

7

Kamchatskaya Oblast

370

359.2

Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy

1740

26

10

130

8

Republic of Sakha (Yakutia)

3,103.2

982.4

Yakutsk

1632

389

30

126 (1400)

9

Chukotskiy Autonomous Okrug

737

68.2

Anadyr

1648

23 (82)

-

64 (80)

Immovable cultural heritage of the Far Eastern District (Table 1.1), besides archeological monuments, is related to 1) the history of exploration and land development by Russian pioneers, who established and developed handcrafts, industries, and trade; 2) the history and culture of Russian migrants from the central Russian regions; and 3) as the history of indigenous peoples.

The development of the territory of the Russian Far East began as early as the seventeenth century. By its middle, the first units of land explorers reached the seacoast of the north-east of Siberia, explored the Lena River, and came to know about the Amur River. At that time, discord with China did not make it possible to move freely along the Amur River; therefore, the Northeast and its unknown regions of Yakutia became the main direction for exploration.

With the rise of Peter the Great, who opened the gate to enlightened Europe, Russian people were inspired to discover new lands, not only to enrich the state treasury, but to conduct scientific research and to meet the interests of Russian trade and industry. The governmental expeditions of the time brought the most important geographical discoveries: the Aleutian and Kuril Islands, the coast of northwestern America, and Sakhalin Island.

In 1860 Russia received the lands of Amursky Krai from signing the Aigun and Peking Treaties. The empire got the opportunity to take advantage of warm sea harbors; entrepreneurs received a way for easy and profitable trade with China, Japan, Korea, and America.

All this became possible through the energetic measures of East Siberia Governor-General N.N. Muravyov-Amurskiy, a great Russian public figure and leader of the great exploration of new lands. In his 13 years of service, new cities rose along the Amur River: Blagoveschensk, Khabarovsk, and Nikolayevsk. The sea fortress and port of Vladivostok were founded in the south, at Peter the Great Gulf. N.N. Muravyov-Amurskiyís activities ended with the constructionóstarted in 1891óof a grand railroad, inspiring new life in Amurskiy Krai. The great Trans-Siberian Railroad connected Russiaís heart with the easternmost point of the country, Vladivostok. The distance between Moscow and Vladivostok is 9288 kilometers.

Primorskiy Krai, whose capital is Vladivostok, takes an intermediary historical and geographical position among such powerful cultural and historical Pacific centers as China, Korea, the Amur River basin, and Japan. Through all historical epochs, this region was on one hand a buffer zone and, on the other hand, a pass for migrating tribes and peoples. Hundreds of archeological monuments are mute witnessesósometimes the only onesóof historic events of great significance.

Primorye is an integral part of Russia, but its history is closely connected with the history of East Asian peoples: minorities of the Russian Far East, as well as the peoples of China, Korea, and Japan. Moreover, there is evidence that ancient tribes from Primorye participated in the race-formation processes of the indigenous population of the American continent. Therefore, many regional archeological monuments are of international significance and provide insight into the historical processes that took place in the Pacific Rim.

The population of Primorskiy Krai is mainly comprised of the descendants of migrants from the central part of Russia (Arkhangelskaya, Voronezhskaya Guberniyas and other regions) and Malorossiya (Ukraine). There are people of 119 different national origins in Primorskiy Krai, 70% of whom are Russians. Representatives of every ethnicity contributed to the general culture of the region. As time passed, the architecture of Primorye acquired ethnic traditions, brought by migrants, as well as motifs of Asian architecture. The appearance of these motifs is explained by their suitability to the peculiarities of the climate and by the areaís general artistic interest in Oriental dťcor. Indeed, Primorye and the Russian Far East contain a great number of outstanding examples of Mongol and Chinese architectural elements in constructions by Russian architects. This characteristic distinguishes the regional architecture.

The quick development of entrepreneurship and trade in Primorye drew the attention of famous European and American companies as long ago as the nineteenth century. The emergence of well-to-do clients attracted renowned architects for the construction of residential mansions, trading houses, educational and municipal institutions, and public buildings. The stateís permanent attention to the development of the region and the defense of its territory made possible big state orders for construction and the engagement of specialists of high quality to carry them out. All these factors allowed for the distinguished architectural build-up of the main cities of Primorye (Vladivostok and Ussuriysk) by 1914.

Of the cities of the Russian Far East, the most significant cultural heritage belongs to the cities of Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Ussuriysk, and Blagoveschensk. In these localities, downtown ensembles, highlighted with stone buildings of high architectural value, were formed in the late-nineteenth to early twentieth centuries.

2. Foundation and Growth of the City of Vladivostok

Europe came to know of the land where the port of Vladivostok would emerge after a French whaleboat visited the place in 1851. The Russian government decided to build up a military outpost there because they sought the best place to shelter a naval flotilla and stay for the winter. The first Russians sent to construct the outpost landed on the Golden Horn coast on June 20, 1860. The Southern Harbors Department was transferred to Vladivostok from Nikolayevsk-na-Amure in 1864, and a year later a shipbuilding yard was opened.

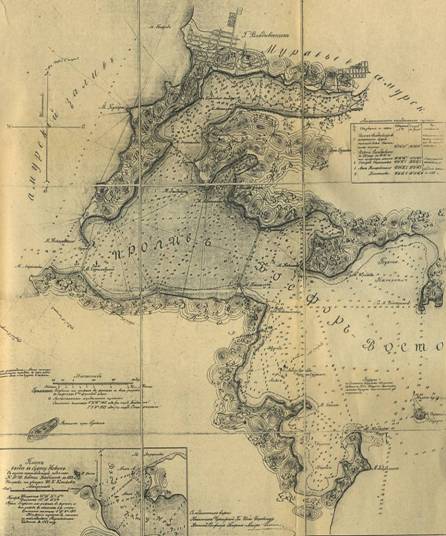

According to Town Construction Instruction, issued in 1864 by Primorskaya Oblast Military Governor N. Korsakov, the local land surveyor M. Lubenskiy was to map out three settlements, Khabarovsk, Nikolayevsk-na-Amure, and Vladivostok, taking into consideration the existing constructions. Lubenskiy drew up the plan in 1868 (Fig. 2.1). The plan for Vladivostok was done in the layout typical of the time: rectangular blocks and streets crossing at right angles. In 1871 and 1872, the Navy Port Administration and the Siberia Flotilla main base moved from Nikolayevsk-na-Amure to Vladivostok. In 1880, Vladivostok acquired official status as a city and was separated from Primorskaya Oblast as a military governorship.

The city started to grow rapidly after 1880, necessitated by its strengthening as a military outpost (Fig. 2.1). A regular boat service from Odessa to Vladivostok launched, the decision to make Vladivostok a Trans-Siberian railroad terminus was promulgated, and the cityís population greatly increased. In 1883 the population of town was 10,000; in 1886 it had grown to 13,000 inhabitants. The machine plant that started to go up in 1883 on the northern shore of Golden Horn Inlet later turned into Dalzavod, the largest enterprise in the Russian Far East.

The military governorship having been abolished, the city was incorporated into Primorskaya Oblast again as its administrative center, and the governorís residence was transferred from Khabarovsk. Nevertheless, in August 1889, Vladivostok was proclaimed a fortress, increasing its significance in the Far East. Cesarevitch Nikolai, later known as Nicholas II, visited Vladivostok in 1891. The would-be emperor proclaimed the foundation of a dry dock in his name (this dock is still in operation) and announced the plan for the eastern part of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. These developments all intensified the strategic importance of the city.

The railroad construction the city launched in May of 1891 became one of the landmarks in the late-nineteenth century. Other landmarks for the city included the opening of a new commercial port and the beginning of regular freight and passenger traffic, in 1897, by the Ussury railroad up to Khabarovsk. Since the shipment of construction materials was mainly by sea, Vladivostok rapidly built up its port capacities.

However, the situation changed drastically at the end of the century. Russia secured the long-term lease of the Liaodong Peninsula, and the State Treasury allocated money for constructing southern ice-free ports. Vladivostokís development came to a standstill.

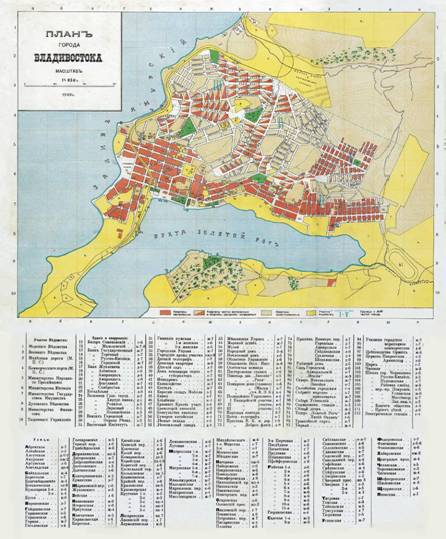

The 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War brought great changes. Russia lost Port Arthur and Dalniy (Dalian), the main competitors with Vladivostok. Gradually, Vladivostok turned into a large European-type center for culture, trade, and industry in the Russian Far East. (Fig. 2.2)

After the shock of Russiaís defeat in the war, and having put down the revolutionary uprisings, the city intensified construction work. The building of the naval fortress, with its forts, coastal batteries, munition depots, and fortress roads, became the most intensive project. It was in this period that the Vladivostok fortress was generally finished.

The civil war halted construction activities, but its end brought a new phase of city development. The Russian Communist Party Central Committee resolved, in 1931, to reconstruct the 12 major Soviet cities, including Vladivostok. This new impetus spurred renewed development.

In 1932, Japan occupied Manchuria, breaking the 1922 agreement. This stimulated the decision to establish the Pacific Navy, thus turning Vladivostok into the major navy base in the Russian Far East. The Vladivostok fortress constructions, which had been abandoned, were employed anew. Coastal installations and piers to moor men-of-war were built. A shipbuilding and repair base grew at Golden Horn Inlet and Diomede and Ulysses Bays.

Country authorities began struggling against religion in the 1930s and 1940s. In Vladivostok, the Assumption of the Mother of God Cathedral and the Holy Virgin Intercession Church, which were pivotal elements of the downtown architectural composition, were barbarously destroyed. In addition to those outstanding buildings, the city was deprived of many other churches that used to decorate the landscape.

By 1939 the population of the city had reached 206,000. New areas of the city were planned in accordance with the first complex master plan, ďGreat Vladivostok,Ē executed under the direction of architect-engineer E. Vasilyev. However, World War II prevented the implementation of many interesting ideas.

Fig. 2.1. 1885 map showing a net of streets planned according to the general plan by Lubenskiy, 1868.

Fig. 2.2. The 1909 layout of Vladivostok.

In October 1959, Nikita Khruschev, Chairperson of the USSR Council of Ministers, visited Vladivostok and envisioned a new role for the city. He vowed to turn it into a new San Francisco. On the instruction of the countryís leader, a commission headed by V. Kucherenko, the USSR Gosstroy (State Construction) Chairperson, was sent to Vladivostok to outline the major lines of city development for the near future (that is, until 1965).

The commercial port, which is of great significance in the Pacific, reclaimed its international status. At the same time, Vladivostok had become the Soviet gateway to the eastern seas. The 1970s and 1980s brought large-scale civic construction, extending the cityís territory.

Vladivostok functioned as a real capital city in the early 1990s. It was an administrative center, a marine commercial port, one of the largest transportation junctions, and a center for fishing and ship-repair. As a cultural and educational hub, it served the entire Russian Far East. It developed as a tourism center and holds a unique resort zone. Simultaneous with all these characteristics, the city retains its historical function as a national naval base. Its current population counts 620,000 residents.

3. Vladivostok Architecture

The historical center of Vladivostok is located on the southernmost end of the Muravyov-Amurskiy Peninsula, washed by Amurskiy and Ussuriyskiy Bays, on territory with a unique natural landscape inseparable from the city history. Until the 1980s, Vladivostok architecture did not dominate the landscape. Buildings coalesced, emphasizing beauty. The city architecture took advantage of the landscape, raised due to the configuration of terrain, or suddenly opening above, behind the turn of a steep street (Fig. 3.1). Although today many topographical formations are hidden among city constructions, the skyline of the city remains unchanged (Fig. 3.3).

The original natural scenery and sea panoramas surrounding the built environment are Vladivostokís most precious property. Generally, all buildings, blocks, and architectural complexes can be seen not only from their street fronts, but also from the mountain peaks and upper slopes (Fig. 3.1, 3.3). One superb feature of Vladivostok is the ability to view, just from Golden Horn Inlet and the Goldobin and Shkot Peninsulas, the city buildings amidst the hills that create a grand rhythm of natural topography.

The downtown city plan has not changed. Historical ward size has been preserved, with buildings of appropriate sizes harmonized with the landscape. The system of gardens and squares, designed before 1920 and completed in the 1950s, has determined the spatial composition of the unique downtown neighborhood.

Fig. 3.1. Mordovtseva St.

Fig. 3.2. The 2004 layout of Vladivostokís historic downtown.

Fig. 3.3. Panorama of historic downtown and Golden Horn Inlet. Vladivostok Train Station, 1912, is in the forefront. Architect V. Planson. (2 Aleutskaya St.)

Fig. 3.4. The beginning of Svetlanskaya St.

Fig. 3.5. Svetlanskaya St. Complex, Kunst & Albers Trade House buildings (1900-1907).

Fig. 3.6. Svetlanskaya St. Vladivostok Post and Telegraph Office (1899), architect A. Gvozdziovskiy. Valdenís House (early 20th century).

Svetlanskaya Street is the cityís main street. It stretches from Amur Bay along the Golden Horn Inlet to its western end. By 1922 the architectural complex of Svetlanskaya Street had been formed up to Kluchevaya Street. It was mainly composed of major festive buildings (Fig. 3.4, 3.5). The two sides of the street are developed differently, though. The northern side is full of monumental buildings, whereas the southern side has open, verdant spaces that separate buildings from each other at a great distance.

The very first plan for the cityís development implies that this uneven development of the two sides was an intentional decision that provided for a view of Golden Horn Inlet to the south. The buildings and complexes south of the street, between the street and the water line, do not interfere with the view, as they are shorter and built down the hill. The northern side of the street is supplied with a system of small gardens, street pockets made in a natural rhythm in place of former ravines.

Streets going down the slopes perpendicular to Svetlanskaya Street did not end in major buildings for the most part. All of them are instead directed to Golden Horn Inlet, the centerpiece of the city. Monuments, silhouetted against the sea and the Goldobin Peninsula, mark two places in the axes of these street networks. In the Soviet period, this city-planning tradition was upheld by building the monument to the Fighters for the Soviet Power in the Far East on the axis of the Okeansky (Ocean) Avenue in the cityís central square, located in the place of the former city garden.

The building complex of Svetlanskaya Street blends with the space of Pushkinskaya Street. The administrative and public city center was originally located here, and the ensemble of building with a system of dominants and co-coordinated architectural accents was generated and kept till our time.

The historic downtown of Vladivostok reveals all the architectural styles that were used by city architects, ranging from neo-Classicism of the late-nineteenth century to modernist styles and neo-Classicism of 1930-1950 (Fig. 3.6). Many outstanding architects, well-known in Russia and abroad, worked in Vladivostok: A. Gvozdziovskiy, H. Junghaendel, Shebalin, I. Meshkov, S. Vensan, A. Bulgakov, N. Konovalov, Y. Shafrat, Y. Wagner, V. Planson; in the Soviet period, A. Zasedatelev, A. Poretskov, L. Butko, and others. Works of some of them are shown in this paper.

4. Immovable Cultural Heritage of Vladivostok

The city and its environs contain a rich and diverse historical and cultural heritage. The number of cultural heritage items is as follows: 579 of local significance, 127 of federal significance, and 38 of archeological significance.

The spatial composition determined by the historical system of streets and squares and the scale of blocks and buildings remains. Almost fully preserved are entire downtown blocks, including the first buildings in the area of Pushkin St., Vsevolod Sibirtsev St., Lutskiy St., and Klyuchevaya St. The built ensemble of Svetlanskaya St., the historical environment of Aleutskaya St., the built ensemble of Pushkinskaya St., Ofitserskaya Sloboda are also intact and well-preserved. Barracks camps of the Military Department remain on Davydov Street, Borisenko Street, and Russkiy Island. Though they are intact, urgent measures are required to restore all of these structures in terms of engineering, foundation protection, renovation of utilities, and renewal of roofs and facades. The outstanding architectural monuments are mostly preserved. However, some Orthodox churches and certain buildings that interfered with implementing new town-planning ideas in the 1970s were pulled down.

There are certain buildings beyond the downtown that are outstanding architectural monuments. These are resorts and health centers, including the institution for mud-cures in Sadgorod, where mud baths were open as early as the nineteenth century. The resorts Primorye and Okeanskiy voyennyi sanatoriy (military resort) are monuments of the 1930-1950 period, and are magnificently adapted to the landscape.

The worldís largest marine fortress complex is a monument of federal significance. The current complex has preserved and includes the following: 44 coastal batteries, nine ground force batteries, two fortifications, two redoubt, six strongholds, 16 forts, four casemated powder-magazines, 12 tunnel powder-magazines, 15 anti-assault caponiers and semi-caponiers, a cold storage, a cable road station, and four Soviet coast batteries constructed in the 1930s that defended Vladivostok from the sea.

The list of architectural monuments in Vladivostok includes a great number of industrial structures: the refrigerated storage Union, the locomotive shop at Pervaya Rechka railroad station, Stalin Tunnel between railroad stations Lugovaya and Tretya Rabochaya, a water tower at the Vladivostok railroad station, the main fire-fighting station, the dry dock named for Cesarevitch, and other unique constructions in the Russian Far East.

Memorials in the area include the Marine Cemetery, which contains the memorial to the perished seamen from the cruiser Varyag, V.K.Arsenyevís grave, and a memorial to Czech and Canadian legionaries. The downtown neighborhood has a number of monuments, including one at the burial site of Count Muravyov-Amurskiyís remains, which were brought from Paris. In the area also are the first city monument to Admiral Nevelskoy and a modern monument to the Fighters for the Soviet Power in the Russian Far East. A talented work of the sculptor and architect that has turned into a symbol of Vladivostok, an A.S. Pushkin bust exists, made by the well-known Soviet sculptor Anikushin. These are several examples of monuments that are of artistic and historical significance.

The natural and anthropogenic landscape of Vladivostok is closely associated with the perception of Vladivostok as a historical city. As a result, the historical skyline of the city is being preserved. It should be noted that between 1970 and 1990, thoughtless construction caused a lot of damage to the historical visage and landscape. Many panoramic sites are preserved nonetheless: Naberezhnaya Street and observation points on Orlinaya and Pochtovaya Mountains. The landscape continues to dominate the buildings that carpet the hill slopes. The terrain is only really shown up by certain structures: outstanding architectural works.

Archeological monuments of Vladivostok and environs represent all historical epochs, ranging from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages. The area of Vladivostok and its environs, though relatively well-researched as to its identified archeological monuments, is a prospective place for future archeologists. Only areas along highways and country roads are well-researched; other territories await thorough archeological exploration.

The agglomeration of the city of Vladivostok (Nedezhdinskiy, Shkotovskiy Rayons, and Artyom) is an active economic zone, which threatens preservation of the archeological objects located in desirable residential and commercial areas. Both unknown and discovered monuments are being destroyed. Particular threat comes from mass privatization of installations and land plots. Development also speeds the exposure of archaeological evidence to the elements. All of these factors make full-scale archeological research of the area urgent.

5. Vladivostok Fortress

Vladivostok Fortress is one of the most significant tourist objects in eastern Russia. It is a unique defensive and historical monument, and the military engineers who constructed it contributed to the cultural heritage of the rest of Vladivostok. The defensive structures are larger than todayís urban construction area, being about 100 kilometers in perimeter and covering 37 kilometers from the northernmost to southernmost points (Fig. 5.3).

There has never been a war operation on the territory of Vladivostok, yet, just by its existence, the fortress saved Vladivostok. In the early twentieth century, Vladivostok Fortress was considered the strongest naval fortress in the world. It was founded to protect the naval base and city of Vladivostok, and it is located on the Muravyov-Amurskiy Peninsula, Russkiy Island, Elena Island, and Shkot Island. It operated formally for 34 years, from 1889 to 1923.

The fortress fortifications, constructed during the years 1910-1917, in view of the Port Arthur heroic defense, had no analogs in the world practice at the time. Some engineering decisions were 10 to 15 years ahead of the timeís military strategies. These strategies included the wide and extended sequence of forts, precise adaptation of their forms to the landscape, and creative, anticipatory design to defend against the largest-caliber artillery shell attack. Some of the engineering designs anticipated conclusions that only broadly arose after the experience of World War I. Foreign experts who examined the fortress in the years 1918-1922 acknowledged that its fortifications were ďa miracle of engineering.Ē The 1995 decree of the Russian president declared Vladivostok fortress fortifications to be monuments of federal (that is, universal Russian) significance.

Decommissioned fortifications that have lost their military function have commonly been turned toward the purpose of tourism throughout the world. The remaining Vladivostok fortress fortifications are architecturally expressive (Fig. 5.4, 5.5), with the majority of them located in suburban forests, on mountaintops, and on the coast (Fig. 5.1, 5.2). Many of these fortifications have branching underground passages and various casemated shelters (Fig. 5.6). All these features contribute to the unique value of the remaining fortifications for tourist and recreational employment.

Fig. 5.1. Fort Russkikh (Fort of the Russians), 1895-1902. Work done by military engineers Romanovich and E. Maak.

Fig. 5.2. Fragment of the gun-pit for the semi-battery Larionovskaya-at-the Peak (1902). Military Engineer E.O.Maak

Fig. 5.3. General layout of the Vladivostok Fortress (1916). The plan copy was made by N.B.Ayushin, based on the archive materials.

Fig. 5.4. Fort # 4, 1910-1917. Military engineer E. Protsenko. A double counter-scarp caponier (coffre) in the ditch

Fig. 5.5. Fort # 4. A rifle parapet and exits from the gallery beneath the parapet

Fig. 5.6. The plan of Fort # 4.

o Ė barbed wire obstruction; g Ė gorge caponier; p Ė postern; ct Ė caserne tunnel; c Ė caserne; t Ė open fire position for flanking guns; oc Ė observation cupola; b Ė barbette; s-rp Ė rifle parapet with gallery beneath it; m Ė moat; a Ė counter scarp caponier (coffer)

Drawing by Volobuev S.A. from materials of RSMHA and field investigations.

6. Heritage Preservation Law

In Russia, cultural heritage is regulated by the 2002 Federal Law, ďOn items of cultural heritage (monuments of history and culture) of peoples in the Russian Federation.Ē This law replaced the 1978 RSFSR Law, ďOn protection and use of historical and cultural monuments.Ē

To enhance cultural heritage preservation in the Russian Federation, a new federal organization was established in 2004 with the Ministry of Culture: the Federal Service to Control the Observation of Federal Laws in Mass Media and Cultural Heritage Preservation (Roskhrankultura). A Roskhrankultura office was established in Primorskiy Krai. The division is responsible for protecting the monuments of federal significance and enforcing laws regarding heritage of regional and municipal significance. Because only the new law of 2002 addresses monuments of local (municipal) significance, the Russian Far East and Primorskiy Krai monuments are not subdivided into regional and local monuments.

A Methodological Commission of Experts has been formed with the Primorskiy Roskhrankultura office. The commission includes honorary experts in town-planning, architecture, and monument preservation, as well as archeologists. The members of the commission examine and discuss all questions concerning protection and restoration of federal monuments. Based on the expertsí opinion, Roskhrankultura makes the necessary decisions.

To control state-owned monuments of federal significance, the federal state culture establishment Agency for Control and Use of Historical and Cultural Monuments (FSCE ACUHCM), under the Ministry of Culture and Mass Media, was established in 2002. The Far Eastern Federal District branch of this establishment was formed in Vladivostok in 2004. The tasks of the establishment are as follows: providing for the correct use of monuments, concluding lease documents, collecting monument money from the leases, and spending this money on conservation and restoration of items.

At present, the FSCE ACUHCM is responsible for thirteen sites of the Vladivostok Fortress; a resolution is pending on assigning 70 more fortress installations to its care. Since the time of its establishment, the branch of FSCE ACUHCM has succeeded in inventorying cultural heritage items, including them in the immovable property register, making topographical maps, determining borders of protection zones and territories, and searching for potential holders.

The law currently in force charges the administrations of the Federation subjects with protecting monuments and carrying out protective measures: controlling town-planning, restoration, and preservation; coordinating project documentation for restoration projects; highlighting and researching monuments; issuing monument passports; implementing preservation zone projects; and controlling owners and users maintaining regional monuments.

The Department of Culture, Primorskiy Krai Administration, is a local body for preserving monuments. The Primorskiy Krai Law on Cultural Heritage Objects has been passed by the Legislative Assembly and is in force on the territory of Primorskiy Krai. The law determines the procedure of monument protection and preservation.

Municipal administrations provide for the maintenance of municipally-owned objects, restoring them in a timely fashion, and improving land. They also control enforcement of the law in the preservation of the historical environment for monuments in the city. In restoration projects, the condition of cultural heritage items is examined. Measures for preservation, especially for preservation of the authentic constructions, fragments, and decorations, are then specified. In some cases when it is otherwise impossible to save the building, hidden inner structures are replaced with modern ones. All these measures are implemented under the supervision of the state (Kraiís) agency for monument protection, whose functions are performed by the Department of Culture, Primorskiy Krai Administration. Every year the cityís administration spends about $1 million for this purpose.

The Vladivostok administration has organized the general town-planning scheme. The plan includes developing monument preservation zones, which will determine: the general requirements for providing the best views of the monuments, the cityís historical environment, observation points, and the historical landscape when new construction and other activities take place in the city.

In 1989 fortress-enthusiast researchers formed the club The Vladivostok Fortress. A new generation of young people continues to study the fortressí history and the 1930s Pacific Fleet coastal defense, discovering new chapters in history. The club members provide invaluable assistance to state and municipal agencies and do a lot to popularize the fortress monuments, attracting tourists.

The Primorye Department of the All-Russian Society for Preservation and Use of Cultural and Historical Monuments functions in Primorskiy Krai and Vladivostok.

7. The Development of Preservation Practice in Primorskiy Krai

Questions of objectsí preservation arose for the first time in Primorye territory and Vladivostok at the end of the 1950. At that time the legislative base was a statute on the protection of cultural monuments, maintained by a resolution by the Council of Ministers of the USSR in 1948. A similar resolution from the Council of Ministers of the RSFSR (the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic) was accepted elaborating on this document. Adoption of a 1976 law, ďOn the protection and use of historical and cultural monuments,Ē was a great step forward.

For the first time, some monuments in Primorskiy Krai came under national protection by the decision of the RSFSR Council of Ministers in 1960. After that, objects of cultural heritage value in the city were protected through the decisions of the executive committee of the Council of People's Deputies in Primorskiy Krai, Krai's Duma, the governor of Primorskiy Krai, and the president of the Russian Federation. In all, protection decisions were made 14 times up to 2000.

The All-Russia Society for Protecting Historical and Cultural Monuments had the leading role in registering monuments up to 1989. The state body for preservation had minimal staffing for the discharge of these functions and leaned on the knowledge of the societyís members. A special group was created in 1989, the Research-and-production center for protection of monuments (RPC). During the existence of RPC, significant research and registration was accomplished while also establishing protection zones and controlling conservation and restoration projects. In 1998 the governor of the region approved temporary zones for protecting historical monuments and the historic center of the city.

In Vladivostok after the revolution (the years 1918-1990), old buildings very seldom underwent thorough overhaul. Those buildings that were renovated lost many valuable elements and details, usually finishing elements on roofing (marquees, turrets, domes, etc.). In the 1930-1950 period many buildings were built with one or two floors. The monuments of architecture that were not touched by repairmen, despite their bad technical condition, have retained all the architectural and decorative elements in their original forms.

With the beginning of political reorientation in 1986, economic stagnation left no means for full-scale repair. At this time many houses were vacant, their technical condition critical. The question frequently arose as whether to tear down these monuments, especially those that posed danger to people. Besides the danger, they spoiled the visage of the city center. Yet these are now the outstanding architecture like the Merchantís Assembly, the Golden Horn (Fig. 7.1), Central Hotel (Fig. 7.2), Salesmanís Assembly (Fig. 7.3), and A.B. Filipchenkoís tenement house, from which one wall of the main facade was kept.

From 1995 to 2000, the new owners of these structures had to carry out large-scale conservation and salvage operations: strengthening the foundations, strengthening bearing walls with metal and ferro-concrete bandages, fully changing overlappings, etc. Compromise was necessary in the process. For example, it was necessary to agree with the desire of the proprietor to not recreate the original interiors in the Gold Horn, which had stood in ruins for more than 10 years as the owner wished to use it as a shopping center. However, the rich decor of the facades, previously lost, has now been restored in full.

The faÁade of Hotel Central has lost most of its original ceramic tiles because of revetments and the fastening of ferro-concrete belts. The tile managed to be preserved around only a few windows, and the owners did not have the means to fully restore the faÁade; city and regional budgets could not help them. However, the turrets and marquees on the roof, disassembled in the 1960s, have been reconstructed.

The 1993 restoration of the Versaille Hotel (Fig. 7.4) is the first full restoration in the city. The building lay vacant for three years after a fire, which partially destroyed interior stucco moldings. As a result, it was possible to restore, in an original form, facades (except for some window fillings) and some interiors: the lobby, foyer, a staircase, and halls of the restaurant. The guest rooms were partially re-planned and equipped with modern engineering systems. Their interiors were not kept.

The lost stucco molding has been replaced, but not well. The owners of the building sought to reduce costs by involving a Chinese contract organization. Communication between the Russian architects and artists with the Chinese workers was extremely difficult. Much had to be altered, especially the interior color scheme. Victor Obertas, the chairman at the time of the Far Eastern branch of the All-Russia Society for Protecting of Monuments (RCP) supervised the project.

RCP also supervised restoration of the House of the Military Governor of Primorye in 1995. After the revolution this monument was used for state and public functions. Many interior details (a stucco molding, fireplaces with the forged lattices, etc.) had been lost by the time of a repair effort in 1980. RCP had to negotiate extensively to ensure that the 1995 efforts were true to the original building and materials. As a result of the RCP requirements practically all materials are authentic to the buildingís period, including wooden fillings on windows and doorways and a recreated canopy above a domestic terrace. Cast pig-iron elements have been replaced but simplified, in spite of the fact that enough of the original ironwork details remain for their design to be copied.

Grandiose works were conducted around the same time on a federally significant railway station building. The Vladivostok train station exemplifies a well-done restoration project (Fig. 3.3). The train station was built in a Russian architectural style in 1912 by the design of architect V.A. Planson. This stylistic decision was approved by the czar to be applied to all train station buildings along the Trans-Siberian railroad in order to symbolize the triumph of Russian imperial power in the illimitable space of Siberia and the Russian Far East.

The train station building was restored in 1994. Vladivostok architects A.I. Melnik, V.I. Smotrikovskiy, T.A. Tkachova designed and supervised the restoration. General work was done by the Italian company Tegola Canadese. Ceramic panels on the facades were restored and ceilings painted by the local artists L.V. Smirnova, T.G. Limonenko and V. F. Kosenko. During the restoration, the bases of the building were strengthened so that bridging beams of the floor deck that were in an emergency state were replaced; metal grids on the roof were restored according to the discovered old fragments and old pictures; the roof was completely replaced; and ceramic plates in the restaurant interior and floor plates were almost fully replaced. It is interesting to know that new floor plates were ordered from the same Italian factory that had produced the original plates. Modern ventilation systems operate in the building, the equipment hidden in the roof space. Lacking are the plastic window reliefs and the mirror glasses, which have slightly altered the original impression of the monument.

For the period of 2005-2006, the Far Eastern Federal District branch of FSCE ACUHCM has been restoring wooden architecture located in its office. Fundamental work has proceeded in changing rotten logs (about 50%), replacing the roof, restoring interiors, and reconstructing carved decorations on facades (Fig. 7.5, 7.6).

There were very few wooden buildings in Vladivostok. Those that did exist were in poor condition, and served as housing for only the poor. Therefore, each example that did remain gradually acquired greater cultural value as rarecarriers of national features in architecture. Today some of outstanding monuments of architecture are completely restored and in good condition. Facades are already repaired on 25, and three are under restoration. Other buildings wait their turn. Recently, the administration of Primorsky Krai announced a design competition for the complex restoration of one of the significant monuments of architecture in which a state gallery and museum will reside.

Each of the mentioned buildings and many other Vladivostok monuments are located in the historical city center. Returning these works to their original countenance has strong public support. Citizens as well as authorities are convinced that improving the condition of historic structures will attract tourism and positively influence the general mood of the city. The Primorsky Krai governorís economic development strategy for 2004-2010 focuses on the development of tourism, preservation, and the rational use of cultural heritage. Preservation of the original appearance of Vladivostok, then, is urgent for the economic well-being of the city, Krai, and the entire Russian Far East.

The economic activity of many enterprises of the city, Primorskiy Krai, the Russian Federation, and various international enterprises is directly dependent on the appearance of Vladivostokís historical downtown district. Company directors tend to have their offices there as well. The location lends legitimacy, for it speaks of a companyís solid profits (as real estate costs are much higher downtown), steady operation, reliability, and deep roots. Such a company can be dealt with. Moreover, businesses that contribute to downtown cultural heritage preservation prove that they care for the areaís greater good, for no economics can develop without culture. It is the historical features of the city that attract tourists and investment. They are catalysts of cultural and economic exchange, giving ground for new links and cooperation in various fields.

In the historical center, visual appeal is demanded. On the one hand, it is a positive force for preservation, when buildings have the funding for the activity. However, the cost of responsible conservation projects can be prohibitive, and so reconstruction begins. The city holds a number of examples of unauthorized alterations, with the destruction of crowning details on facades. An example is one three-tiered building in a neo-Classical style with elements of baroque, as it is traditionally accepted in Vladivostok, that has been topped by Attic accents. Then, in 2005, a private owner purchased the building, and it acquired glass facades.

The Primorskiy department of Roskhrankultura has since taken measures to stop these kinds of works. The impediments to responsible restoration projects have mainly been:

The insufficient education of builders-restorers.

Proprietors and users do not understand the importance of restoration requirements.

The insufficient quantity of experts in supervising state bodies.

Police and supervising bodies have stepped up their enforcement. Lawsuits are pending. A criminal case has recently begun in Ussuriisk over the destruction of the interiors of a building during repair work. All citizens interested in preservation of cultural heritage anticipate continued progress in the preservation of monuments.

8. Tourism

In 2004 the governor approved and published ďStrategy for the Social and Economic Development of Primorskiy Krai for 2004-2010.Ē In the strategic context, Primorskiy Krai is considered ďthe southern economic and cultural gateĒ of Russia, CIS, and Europe to the Pacific. The first stage (through 2007-2008) has Primorskiy Krai become a recreation and tourist center of the Russian Far East and Siberia. Then, by 2010-2012, it is to become a large international center of ecological technologies and cultural tourism for a number of countries in the Asian Pacific Region.

Among the main strategies for accomplishing these goals is the intention to consolidate the financial means of the economic participants in the recreational and tourist complex and create all-seasonal recreation, amusement, and show opportunities. The following projects remain to be carried out: creation of a unified information and marketing center, construction of a water park in Vladivostok, restoration of the fortress installations, complex recreational development of Russkiy Island, and efficient marketing of the existing monuments of history and culture.

Having been opened for foreign visitors in 1991, Vladivostok is gradually becoming an important site for international tourism. The tourism infrastructure must be improved; it will increase the tourist in-flow to 1-1.2 million tourists annually. The total tourism contribution to the stateís economy will make up over 10 billion rubles.

The city of Vladivostok has a variety of characteristics on which various lines of tourism can be based. Vladivostok and its environs are rich in natural resources: the sea coast, picturesque islands (18), and forests. There are three professional theaters and seven public museums in the city. The transportation infrastructure is reliable. The international airport in Vladivostok makes short flights possible from Europe, America, Japan, India, and other countries. The port of Vladivostok can receive 2,670-passenger Grand Class vessels like the Diamond Princess and the Sapphire Princess. The Trans-Siberian railroad enables transport through Siberia and Central Russia to Moscow and further on to Europe.

The hotel business is a limiting factor. Only 10 of the 55 hotels in Vladivostok can receive foreign guests with international standards. Vladivostok is famous for its resorts, though. As early as the nineteenth century, curative mud baths in the suburbs drew visitors. The Sadgorod mud therapy resort of 1924 is included on the list of sites preserved by the state as architectural and historical monuments. Today Vladivostok has 57 summer and year-round resorts, tourist bases, children camps, and health spas, which collectively receive over 8,000 people. Yearly, 90 to 100 thousand people rest and improve their health there. Residents of the city and the state, as well as visitors from other regions of the country, are presently the primary clients of the recreation institutions. The total potential number of visitors is 40 to 60 thousand people at a time.

Tourism, as a business, is being developed. Currently, 180 tour companies function in Primorye; 120 of these are in Vladivostok. Generally they are aimed to organize exit tourism for the local population (in 2005, 728,100 Russian tourists exited Primorye). However, today entry tourism is actively being developed, and 115,500 foreign tourists came to Primorye in 2005. Foreigners coming to Vladivostok are mostly Chinese, Japanese, and South Korean citizens.

Tourism as a sector of the economy represents the specific intersection of hospitality services, restaurants, transportation, entertainment enterprises, the various firms that organize different tourist activities, excursion services, and the services of guides and translators. The modern tourist industry is one of the most profitable (up to 10% of the Gross National Product) and quickly-developing branches of the world economy. It holds second place in the worldís incomes, yielding only to information technology. Primorskiy Krai is one of the Russian regions where the tourist sector is a priority and can become a specialization of the regional economy. Simultaneously, this branch of the economy directly influences the general social climate, creating a basis for recreation.

The turnover of profits to the branch is approximately 3-5 million dollars. Experts estimate that tourist business makes up 3% of the Gross Regional Product. This is above the average across Russia, but it is considerably below the world index.

The key impediments to the development of increased tourism are:

A low level of capitalization for the tourist infrastructure;

Absence of a united strategy of development, which results in the irrational duplication of tourist programs, investment projects, and dissipation of the limited financial resources. Essentially, as a consequence, there is a general decrease in efficiency of activity in the sphere of tourism.

Absence of a coordinated national policy for the development of marine and ecological kinds of tourism, in spite of the unique tourist resources (sea and river water areas, taiga routes) available. Such kinds of tourism as cruise packages are practically not developed at all.

A low level of marketing and advertising of the tourist and recreational services of region.

The need to revise taxation and the tourist legislative base.

A high level of illegal activity.

A low level of investment accumulation. Currently, the industry cannot develop intensively by leaning on its own accumulation. At the present moment, the total amount of investment in current projects is $438 million.

The lack of co-ordination between the interests of municipal authorities, travel agencies, the users of recreational lands, and local residents.

Only 10% of the recreational potential of Primorskiy Kraiís land is used.

A low level of service and accommodation for guests and tourists. The orientation of the majority of the hotel enterprises is to budget tourists.

The need to revise the economic mechanisms of hotel business development.

Absence of hotel segmentation on various values and tastes.

Poor quality and a low level of differentiation of tourist services.

Poor dining options; 15-25% of tourist costs comes from dining.

Tasks and Objectives

The average expenditure of each foreign tourist is $700-900. Improving the tourism opportunities supplies a growing demand from consumers (both Russian and foreign) for quality, and it also contributes to the social and economic development of the region with an increase in profit, increases in the number of workplaces, improvements in the health of the population, and the preservation and rational use of heritage.

The following tasks must be accomplished to pursue tourism development. First, the infrastructure must be improved to allow for 1.2-1.5 million tourists. This will guarantee 100,000 jobs an inflow of 1-1.3 billion dollars.

Secondly, the duration of touristsí stays must increase. For this task it is necessary to:

create the conditions for the development of multipurpose vacation spots, and to

diversify the tourist programs in terms of the frequency of offerings and the quality of services.

The third task is to speed the improvements of culture and social objects. For this task it is necessary to:

finish renovation of the historical urban environment in the territories focused on the service of tourists;

solve the problem with allotting and reserving territories for ecological tourism;

provide federal status for the historical museum of the military fortress, lead restorative reconstruction, and clear territory from casual buildings;

place special tourist equipment, allowing one to see a panorama of city at any time; and

create a national mini-park on the island Russkiy about Russian history.

The European culture in the region must also be given attention. Tourists from the Asian Pacific region come to see the European culture, art, and architecture. Primorye is an outstanding place of historical inter-penetration of European and Asian cultures. Europeans who visit are similarly interested in the Eastern culture of the indigenous people who populated this territory of Russia in the past. This is why more and more tourists visit Primorskiy Krai. Seventeen foreign consulates and representatives of many foreign companies work in Primorskiy Krai.

Extreme tourism attracts additional tourists to the region: deep-water diving, speleotourism, rafting, hikes deep into the taiga (thick forest) to unique natural objects, and paraplane flights.

Informative excursions (by bus, horse, and walking) to the fortress also attracts tourism. Regularly held at the fortress are various theatrical shows and games for children and students. The natural setting of the monuments makes the tourist potential of these territories especially high (Fig.5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 5.5).

Today the full potential of the fortress complex is not exploited. The challenges for tourism are as follows: the complex is scattered on a vast territory, with many installations located far away from downtown; the fortress dirt roads, which are over 100 years old, need remodeling, making it that much more difficult to reach the monuments; the buildings lack electricity, a water supply, and sewerage. Additional rooms for administration and service personnel are required.

To make matters more difficult, these needs sometimes contradict the requirements for preserving the historical environment of monuments. Yet, the use of the fortress for tourism is of great importance not only for Primorskiy Krai but also for the entire Russian Far East.

As far as the Vladivostok historical downtown is concerned, city guests are primarily interested in the architectural monuments and historical quarters of the city. Among them there are several quarters, including Chinese ones, called Millionka. This is the area bordered by the beginning of Svetlanskaya Street (Fig. 3.4, 3.5, 7.1, 7.2, 7.4), Semyonovskaya, Admiral Fokin, and Pogranichnaya Street. Interesting architectural and spatial environments have made these quarters the most favored places of the city. To fully utilize this area for tourism, we need a complex reconstruction of the quarters with renewed engineering support. Remodeling and partial reconstruction of inter-quarter spaces, to use them for tourism, will increase the influx of visitors and bring profit.

Good examples of the use of cultural heritage for tourism include the following:

Excursions on the history of the city and the fortress should use the work done by the Information and Methodological Tour and Excursion Center with the V.K. Arsenyev Primorskiy Regional Museum. To date the Center has developed 70 thematic tours about Primorskiy Krai. These are in great demand. Forty of the tours are related to the history and architecture of the city and fortress of Vladivostok. To improve and renew tours and to better their quality, the Center holds competitions among the tour guides. The authors of the best excursions are rewarded.

Six monuments of architecture are used for public interest as state museums and a library. Ten more are used as public buildings: a post office, the station, two theaters, two houses of culture, the steamship company, trading houses, etc.

The monument ďFort # 7Ē is an excursion and museum recreational object, located in the outskirts of Vladivostok. It has two-hour walks about the underground installations, so that tourists come out in the ditch and then climb to the mountain top. The view and the experience leaves an unforgettable impression with all visitors.

The Primorskiy Krai branch of the All-Russia Society for Protecting Historical and Cultural Monuments has created a museum of Vladivostok Fortress history based on the coastal battery Bezymiannaya, located in the historical center of the city.

The Naval History Museum of the RF Pacific Fleet, based out of the battery Voroshilovskaya constructed on Russkiy Island in 1932, conducts historical research and tour work.

Informative, educational, and excursion work for the children from riding-school Hypparion is offered at the monument ďStronghold Lettered Z (З)Ē near Fort # 7.

An ecological post that has been functioning on Elena Island for several years combines tourist (mostly children and teenager) coastal beach recreation with excursions to the nearest constructions, coastal batteries Southern Larionovskaya and Larionovskaya-at-the-Peak (Fig. 5.2), and Anti-Assault Semi-Caponier #17.

Anna Myalk is Director of the Federal Agency for the Protection of Monuments, Vladivostok, Russia. Victor Fersht is Chairman, International Association for Joint Programs of United Nations Human Settlement Programs Ė UN-Habitat and UNESCO, Vladivostok, Russia, and Executive Chairman, Best Practices Magazine (UN-Habitat). Victor Korskov is Director, UNESCO Programs, Vladivostok, Russia.

End Notes

Section 1

Russian Federation Ministry of Culture, 2004, information book.

Trofimov V.P., Ilyin A.A (1998) To Meet the Sun, pp. 10-13

Section 2

Myalk A.V., Kalinin V.I. (ed.) (2005) Vladivostok. Pamyatniki Arkhitektury (Architectural Monuments), pp. 5-8

Copies of Vladivostok historical plans were provided by the Central State Historical Archive of the Russian Far East.

Section 3

Myalk, A.V., Kalinin V.I, (2005), Vladivostok. Pamyatniki Arkhitektury (Architectural Monuments), pp 8-11.

Section 5

Kalinin V.I., Ayushin N.B. (1996). Morskaya krepost Vladivostok (Marine Fortress of Vladivostok). In: Vestnik DVO RAN, # 5, pp. 96-106

Ayushin N.B., Kalinin V.I., Vorobyev S.A., Gavrilkin V.N. (2001). St. Petersburg. Krepost Vladivostok (Fortress of Vladivostok), p. 151.

Myalk A.V., Kalinin V.I. (2005), Vladivostok, Pamyatniki Arkhitektury (Architectural Monuments), pp. 149-152.

Section 8

Rosstat (2005), statistic yearbook Primorskiy Krai.

Pacific Center for Strategic Development (2004). Strategy of the Social and Economic Development of Primorskiy Krai, pp. 117-124, 167-172.